April showers may bring May flowers, however I wish the cold would leave a little faster. It’s wonderful to walk in the woods, or even just step outside, and find the sights and sounds of spring bursting into bloom. Despite the chilly weather, all the ponds near my house are reverberating with frog calls, and birds of all shapes and sizes can be seen flitting among tree branches. Early flowers and the first hints of green are also beginning to speckle the woods. This weekend, I came across several dappled patches of trout lilies while out hiking and plan to keep an eye out for their first flowers. If you are interested in wildflowers and recording when they bloom, now is the time to go out and explore!

This Week on Tech Tip Tuesday

This week we’re revisiting a topic I discussed way back in January: using identify. However, today I’m getting a lot more specific. Identify is a great tool for more than just suggesting an observation—it’s also an easy way to add annotations to someone else’s observation. If you need a refresher on annotations, check out TTT #1.

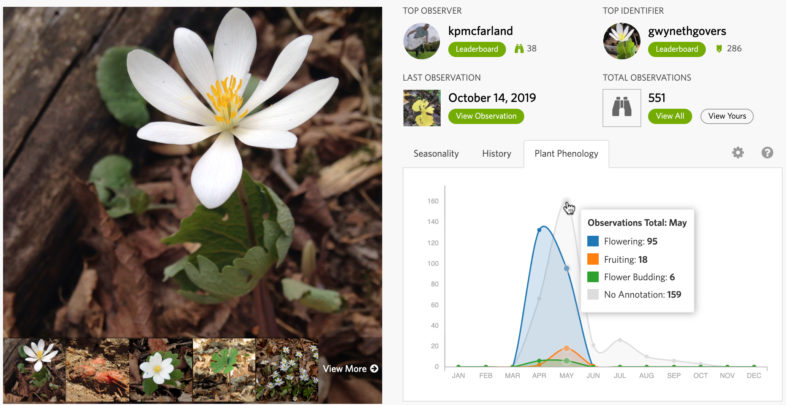

Annotations are important to include year round, however they are especially important in the spring. By tracking when spring wildflowers bloom every year, scientists can gain valuable information about how natural systems are responding to climate change. To read more about why annotating spring wildflowers is important, visit the VCE blog.

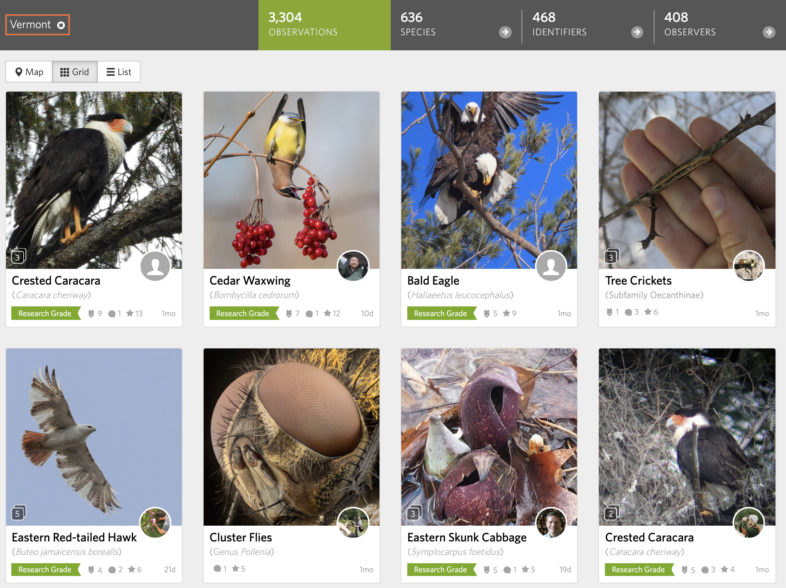

Adding annotations through identify is fairly easy, especially if you’ve already been using identify to suggest identifications. To start, navigate to the identify page by clicking on the tab across the top of your screen that says “Identify”. Once on the page, I recommend starting by entering “Vermont, US” into the place search box and clicking “Go”. This will limit your search to Vermont. Now, if you have a favorite spring wildflower (Red Trillium for example), you can enter its species name into the species search bar, or you can simply type in “Flowering Plants” (subphylum Angiospermae) to see all the flowering plant observations in Vermont.

Once you have those set, it’s time to add some filters to help narrow your search (“Filters” is located to the right of “Go”). The first filter you need to change is the quality grade (located in the top left corner). When you first open identify, it’s automatically set to “Needs ID”, however there are plenty of research grade wildflower observations that need annotations. Under “Quality Grade”, click in the check box next to “research grade”. Now, you will see research grade observations as well as ones needing identification.

Since we’re looking for spring wildflowers, the next place to go is “Date Observed” (top right corner). When you start, it will be set to any, however we want to change it so that it only focuses on spring wildflowers. Select “Months” and click on the dropdown menu. I recommend selecting March through July.

The final key step is to narrow your search to flowers that need annotation. Under “Description and Tags” in the bottom left corner you will see a link that says “More Filters”—click on it. Under this section, go to the middle and click on the dropdown menu under “Without Annotation”. Change it from “None” to “Plant Phenology”, and leave the second dropdown menu set to “Any”.

Once all your filters are set, click “Update Search” at the bottom of the filter box.

Now you should see a grid (or a list or map, depending on your viewing settings) of photos with plants. Not all may be flowering, however if you see anything that looks wildly out of place (a frog perhaps), double check your settings.

To start, click on the first observation. To get to annotations, click on the “Annotation” tab in the menu to the right of the observation’s picture. Two options should appear: “Sex” and “Plant Phenology”. Look at the photo(s) included with the observation—is the plant flowering, fruiting, or budding? Click on the dropdown menu next to “Plant Phenology” and choose the appropriate answer. If the plant didn’t have flowers, fruits, or buds, select “No evidence of flowering”.

You can also make these same selections using handy shortcuts. To view shortcuts, click on the keyboard icon in the bottom left corner of the observation box. Notice that for plant phenology, you can type “p” “l” to mark it as flowering, “p” “r” to mark it as fruiting, “p” “u” to mark it as budding, and “p” “n” to mark it as no evidence.

Regardless of which method you choose, you should see your annotation appear next to “Plant Phenology” with your profile picture. When you see this, you’ve successfully added an annotation and can continue you on to the next one. To get to the next observation, you can either click on the arrow to the right of the observation box or hit the right facing arrow on your keyboard.

Once you get the hang of it, the process is very simple and you can easily fly through observations!

TTT Task of the Week

This week I want you all to take part in our Spring Wildflower Phenology Annotation Blitz. Use the steps provided above to add annotations to wildflower observations and help us better understand how Vermont’s wildflowers are responding to climate change. If you have wildflowers in your yard, I also encourage you to take photos of them over the coming weeks and share those photos with the Vermont Atlas of Life.

Thank you for helping us map Vermont’s biodiversity, stay safe, and happy observing!